22.3.2012 | 14:46

Why Argentina did not have a currency board (myntrįš)

forseti Ķslands | |||||

forseti Ķslands |

Why Argentina did not have a currency board (myntrįš) Fyrst birt ķ tķmaritinu Central Banking Journal febrśar 2008.

Argentina introduced its “convertibility” system, which linked the Argentine peso to the dollar at a fixed rate, on 1 April 1991. The convertibility system ended in a spectacular economic crash and currency devaluation in January 2002. Most economists asserted that Argentina’s convertibility system was a currency board, with little room for discretionary monetary policy. Armed with that premise, other economists and the financial journalists who followed their lead have concluded that currency boards are inherently dangerous and bound to end in Argentine-like upheavals.

Loose charges. In an extensive survey of the works of 100 leading economists who commented on Argentina’s travails, Schuler (2005) found that of the 94 who mentioned convertibility, 91 christened Argentina’s system a currency board. The assertions and policy pronouncements made by these economists were based on loose charges, vague notions and indiscernible facts. In short, they were wrong. Unfortunately, now the standard textbook treatment of the Argentine episode is flawed and the currency board idea is tainted. Just what is a currency board ? It is a monetary authority that issues notes and coins convertible on demand into a foreign anchor currency at a fixed rate of exchange. As reserves it holds low-risk, interest-bearing bonds denominated in the anchor currency and typically some gold. The reserve levels are set by law and are equal to 100%, or slightly more, of its monetary liabilities (notes, coins, and if permitted, deposits). By design, a currency board has no discretionary monetary powers and can not engage in the fiduciary issue of money. Its operations are passive and automatic. The sole function of a currency board is to exchange the domestic currency it issues for an anchor currency at a fixed rate. Consequently, the quantity of domestic currency in circulation is determined solely by market forces, namely the demand for domestic currency.

Like a central bank. Argentina’s convertibility system operated more like a central bank than a currency board in many important respects (see Hanke, 2002). That said, it did mimic some currency board features and could be termed a currency-board-like system. Currency-board-like systems differ most importantly from currency boards with respect to their reserve ratios and their power to act as lenders of last resort. Currency-board-like systems do not have a maximum reserve ratio. In contrast, if a currency board is allowed to accumulate foreign reserves exceeding 100% of the monetary base, the amount of the surplus has a definite upper limit, which historically has been 10%. A currency board is not allowed to use its surplus in a discretionary manner and all profits beyond those necessary to maintain the small surplus must be transferred to the government. Most currency-board-like systems, in contrast, are permitted to accumulate profits (surplus reserves) unchecked (though, in practice, there is political pressure to contribute some reserves to the general government budget). Currency-board-like systems are also allowed to use their surplus reserves in a discretionary manner to act as lenders of last resort to commercial banks. In some cases, they can also use their main reserves in the same manner.

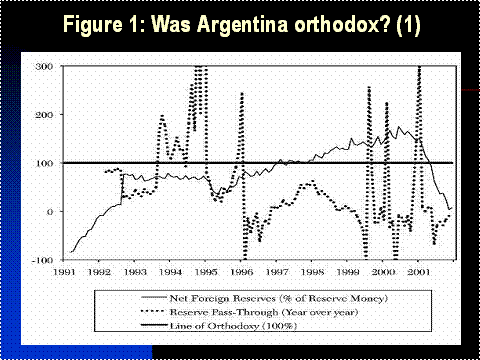

Mischief in bad times. These deviations from currency board orthodoxy can be fairly harmless in good economic times, but cause great mischief in bad times. Argentina’s convertibility system is a classic example. There is a straightforward way to determine, with publicly available data, whether a monetary authority is a currency board or a currency-board-like system. For a currency board, net foreign reserves (foreign assets minus foreign liabilities) should be close to 100% of the monetary base (also called reserve money). Moreover, “reservepass-though” (the change in the monetary base divided by the change in net foreign reserves over the period in question) should also be close to 100%. Source: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics database, August 2007.

More than hair splitting. Over 70 countries have employed currency boards and none has ended with the type of economic chaos that accompanied the demise of Argentina’s convertibility system. But, contrary to the conclusions that most economists and economic textbooks present, Argentina’s convertibility system was not acurrency board. This distinction is more important than a mere splitting of academic hairs. The authorities in several countries, including Georgia, are considering the establishment of currency boards. Unfortunately, discussions of the pros and cons are difficult because the opponents of currency boards drag in fruit from Argentina’s poisonous tree.

References. Hanke, Steve H. 2002. On Dollarization and Currency Boards: Error and Deception, The Journal of Policy Reform, 5 (4). Schuler, Kurt. (2005). Ignorance and Influence: US Economists on Argentina’s Depression of 1998–2002, Econ Journal Watch, 2 (2). Notes. The author would like to thank Kurt Schuler for his comments. (1) Reserve pass-through is the change in the monetary base divided by the change in net foreign reserves. Here, the period is one year, using data of monthly frequency. Argentina’s convertibility system began in April 1991, so the first month of the reserve pass-through line is April 1992. The source of the data is the International Financial Statistics database. The term the database uses for the monetary base is “reserve money”. Net foreign reserves are the foreign assets minus the foreign liabilities of the monetary authority. Sjóšstreymi-hlutfall er breyting peningamagns ķ hagkerfinu deilt meš hreinni breytingu į gjaldmišla-eign hjį myntrįšinu/sešlabankanum. Reiknašar eru breytingar į žessu hlutfalli yfir hvert įr. >>><<< Steve H. Hanke er prófessor ķ hagnżtri hagfręši viš John Hopkins hįskólann ķ Baltimore og heišursfélagi viš Cato stofnunina ķ Washington borg. >>><<< |